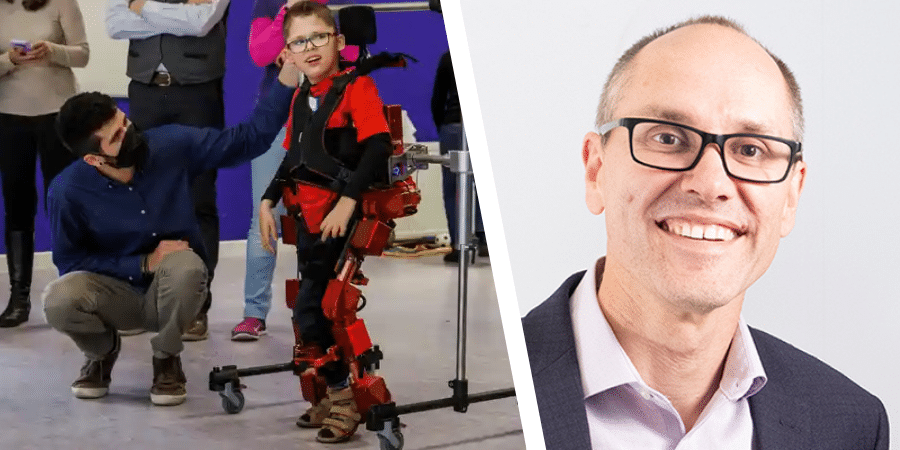

Earlier this month a 12-year-old Spanish boy with cerebral palsy walked and played with his friends using a state-of-the-art paediatric exoskeleton. How close are we to unlocking this kind of assistive technology for others with CP?

Cerebral Palsy Alliance’s Professor Alistair McEwan recently spoke to ABC Radio Sydney to discuss the exciting possibilities that exoskeletons may open up for people with cerebral palsy.

ABC: Do you know anyone living with cerebral palsy? That’s a condition that’s caused by damage or abnormal development in the part of the brain that controls movement. So, what it means is that people with cerebral palsy often require the use of a wheelchair. There are some 34,000 Australians living with cerebral palsy with no known cure.

But last week I read something that made me cry with happiness. There was a 12-year-old Spanish boy with cerebral palsy and on his birthday, in the company of the Spanish prime minister, he was fitted with a state-of-the-art exoskeleton that allowed him to stand up, walk over to his classmates, and play with them.

It gave him this unimaginable movement and freedom to actually be just like the other kids. Such an amazing thing to see, and I wondered if that could happen for children or adults living with cerebral palsy here in Australia. Well, Professor Alistair McEwan is the Ainsworth Chair of Technology and Innovation at Cerebral Palsy Alliance and The University of Sydney. Good morning Alistair.

Alistair: Good morning Renee, it’s great to talk to you – it’s an amazing story, isn’t it, really wonderful to see.

ABC: And so you work with this emerging technology, tell me what are these exoskeletons?

Alistair: It really means taking the human skeleton and placing it outside the body. So, for people who have weaker muscles or movement that they can’t control, if we place a ‘skeleton’, a hard mechanical device, outside their body, like a walking cane but something that is powered and helps them move, then they can move using those devices.”

ABC: This technology has been around for some time, but this particular exoskeleton was said to be particularly unique because of the elastic technology that adapts to the user’s body. Can you explain that?

Alistair: “What they’re talking about there is including a spring inside the motors, so they have one motor that controls the hips, the knees and the ankles, but also a spring within that motor that allows the joints to move side-to-side and hips to open as well as moving backwards and forwards, so that’s what they’re providing. It’s a little like a shock absorber, you can imagine it like that on a mountain bike and things like that, the spring is able to help match that person’s ability and function and that can be adjusted with them as they improve.

A lot of the exoskeletons we see are used in clinics and they’re helping people improve function, but the other amazing part of that story was seeing the exoskeleton come out of the clinic and into the classroom with that young boy. We can see that with some of the people we work with here in Sydney at the Cerebral Palsy Alliance – for the first time with some of these technologies, they’re able to start to do things on their own and have their own independence. We want to move that much earlier in life because as you mentioned, CP happens really early in life sometimes before birth, and we know that if we intervene early we get much better outcomes. We’re really pushing to make [this technology accessible] using sort of ‘soft’ materials, one project we have is an air-powered exoskeleton that’s being developed in Hong Kong. You can think of it as a balloon-like device placed under the knee, and as we inflate that balloon the leg can straighten, and as the air comes out again, the leg can bend again, so we can help kids stand and walk. We’re going to be doing a study here in Sydney [using this device] where we help kids stand and walk, and we’ve already seen in Hong Kong how children can walk using this exoskeleton.

ABC: So what you’re saying here is these exoskeletons come in many forms and the technology is here in Australia, it’s available for kids with CP now?

Alistair: It’s coming at an increasing rate – there’s a wonderful organisation in Wollongong, a start-up called RoboFit Gym at the University of Wollongong site, and they’re bringing in a Japanese exoskeleton from a company called Cyberdyne. It has Therapeutic Goods Association approval now and a paediatric version is going to be available in a few months. There’s also a company that has reached out to [CPA] from the US called BioMotum, that technology has been available for many years at the National Institute of Health there, and they’ve been able to basically put the power supply into a small backpack that the child wears. They’ve got amazing videos of children hiking in tough terrain on their own wearing these wearable robots, and that’s a form of exoskeleton.

ABC: So what sort of cost is involved, because I’m sure some listeners would just think well this would be prohibitive for me and my family…

Alistair: It’s complicated, and it’s even more complicated in the US, so BioMotum wants to come to Australia because of our National Disability Insurance Agency and they’re very interested in that model. That is one way to access these kinds of technologies, though it is up to the person and the plan.

As an engineer I can see this technology is the way to bring the cost down and provide a way to intervene early so that the outcomes for people with CP are vastly different [improved] over the lifetime of the individual. It’s about keeping children out of wheelchairs so their lifetime costs will be less and I think that’s what the NDIS is really about, it’s about those permanent changes so people don’t need as much support and they’re able to be included in society, in education, in work, in all sorts of areas.

ABC: Just to get an idea, is it $20,000, $50,000 to get one of these exoskeletons?

Alistair: It is up above that level at the moment, the BioMotum device will be much less. We can see that the influences are coming from different areas, so it’s amazing that just last year Otto Bock, a company that makes full limb prosthetics, they bought an exoskeleton company from California that was making an exoskeleton for CP, and their clients are companies like Volkswagen, building companies, anyone who’s working above their heads, so they can see an occupational exoskeletons. And what that means is that this tech will be used in many areas, and that will [drive innovation] and bring down the cost. They’re selling those for about $6,000 Euros. The CEO of that company is a professor at Berkeley, and his vision is that those exoskeletons could cost as little as an electric scooter – it’s the same sort of motors, the same sort of cost if you’re making hundreds of thousands of those devices, there’s no reason they couldn’t cost the same as an electric scooter or hoverboard skateboard.

ABC: Obviously it’s life-changing for people with cerebral palsy who are using a wheelchair, but is it just applicable to young people or could adults also use an exoskeleton?

Alistair: That’s right, these devices can be completely personalised to the individual, the types of goals they want to achieve, you may even have exoskeletons for different days or reconfigure them in different ways, depending on what you choose to do. If you’re playing golf one day or not being as active you may choose to use a different type of exoskeleton. And in my research when we talked to people with cerebral palsy we try and consider all the available technologies, so we’re looking at can we take cochlear implant technology and use it to control muscles, as an implant that’s there all the time and available all the time, it wouldn’t need to be charged up like you would an exoskeleton or put it on every day. Or would you prefer to have robot technology in your house to assist you? There are robotic devices now, like our vacuum cleaners, and we’re working with start-ups who are modifying those to do tasks in the home.

ABC: It’s absolutely mind-blowing to think about – we just mentioned a person with cerebral palsy being able to play golf, stand up on a golf course and actually play that game with friends, it’s just so exciting to me. Thank you, Professor Alistair McEwan, – to think that technology is happening right here in NSW is something else, keep working!